(By Rabbi Yair Hoffman for 5tjt.com)

You have taken a job. Your boss, however, is morally challenged – taking dishonest advantage of customers. Are you obligated to quit and find another job?

THREE SCENARIOS

- Your store is running an advertised sale. Every item is 30 percent off. The customer has entered and is unaware of the sale. Your boss has instructed you that, unless they are a regular customer, if a person is unaware of the sale to charge them full price and not tell them. What should you do?

- You work for a school. A wealthy individual buys a house and wants to register his kids in the school. Your boss lies and tells you to say to him that there is no room in the school, and the wealthy person must pay for another classroom if he wants to register his child. You know that it is a bald-faced lie. Are you permitted to convey the message to the wealthy person?

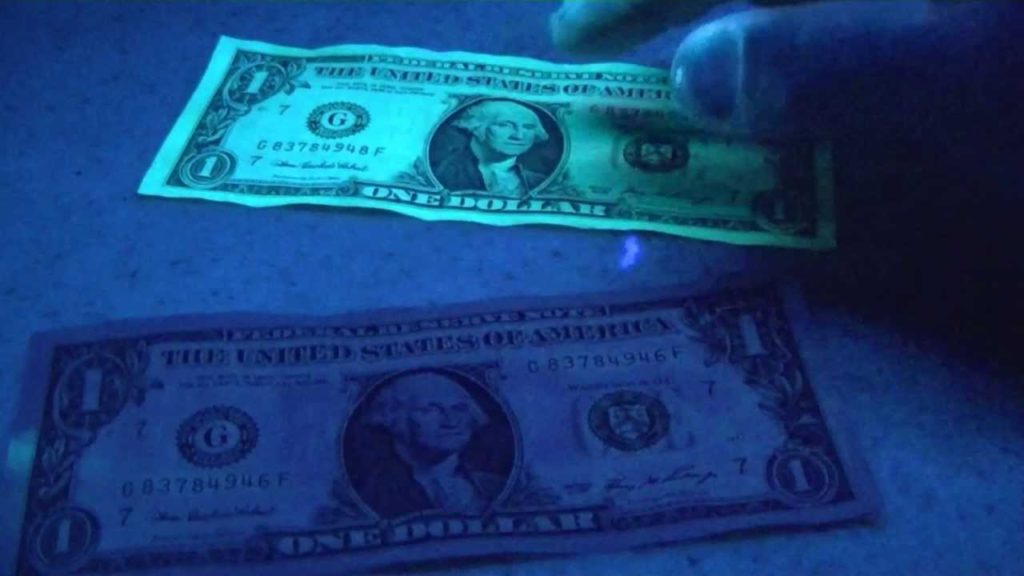

- Your boss has purchased real name brand product and also some counterfeit product that looks almost identical. He tells you to sell the counterfeit brand to anyone who would be unable to tell the difference. Are you obligated to quit your job?

THE THEFT ISSUE

There are a number of issues at play here. Firstly, there may be an issue of partaking in theft. Whenever this happens, the act is strictly forbidden. The Torah absolutely forbids any act of theft – even if one is merely one player in the act.

THE LIFNEI IVER ISSUE

There is another issue of Lifnei Iver – placing a stumbling block before the blind found in Vayikra (19:14). This issue may be providing a stumbling block not only in front of the customer but also in front of the employer himself.

There are three forms of the prohibition of “misleading the blind.” There is (a) the notion of causing someone to stumble in Jewish law, there is (b) the notion of giving someone bad advice, and there is (c) the aspect of physically placing an object before another person that is either harmful or dangerous.

Most authorities hold that one who violates type (a) is also in violation of type (b) (see Igros Moshe YD I #3, Achiezer Vol. III 65:9 and 81:17). It is interesting to note that Rav Moshe Feinstein writes that violating type (a) is a sin between man and Hashem–not between man and his friend (IM OC IV #13).

BOSS IS DOING IT WILLFULLY

But you may suggest that your boss is purposefully violating halacha! That’s not “the blind”–he is stealing with full knowledge! The Rambam addresses this question in his comments to the Mishnah in Shviis (5:6): “This means to say that when temptation and the evil inclination have shut the eyes of an individual, do not assist him in adding to his blindness.”

While this is true regarding willful type (a) violations, it is not so clear-cut regarding a willful violation under type (b)–bad advice lifnei iver. Rav Chaim Ozer Grozinsky (Achiezer ibid) rules that when the “victim” is willfully doing something against his best interests, the Rishonim hold that there is no prohibition. Rav Feinstein, zt’l, agrees. The Rambam, however, rules that there is a prohibition (Hilchos Rotzayach 12:14). Generally speaking, the rule of thumb is to be stringent.

RABBINIC VIOLATION

There is another issue too. The Talmud (Avodah Zarah 6b) explains that the actual prohibition of lifnei iver is violated by the enabler only when the victim could not have violated the prohibition without the enabler. This is called “trei ivrah d’nahara–two sides of the river.” The classical example is of a nazir who vowed not to drink wine, and you are the only person who can hand him the wine, since it is on the other side of the river.

If the wine is on the same side of the river, or–in our case–if there is another ice-cream shop in town, it may involve a different, rabbinic prohibition called mesaya lidei ovrei aveirah–assisting the hands of evildoers.

Who cares whether it is biblical or rabbinical? Well you may, for one. The reason is that the Dagul Mervavah (on the Shach in YD 151:6) holds that when the violator is willful and it is only a rabbinic violation, there is no rabbinic prohibition either. This could perhaps be a factor in whether one may continue working there or not.

TWO CAVEATS MAKING IT BIBLICAL AGAIN

There is a fascinating caveat to all this given both by the Chofetz Chaim (Laws of LH 9:1) and the Chazon Ish (YD 62:13). If the enabler instigated it–it remains a Biblical prohibition!

There is another caveat too. It is known as the Mishnah LaMelech’s Caveat (Hilchos Malveh uLoveh 4:2). The author, Rav Yehudah ben Shmuel Rosanes (1657-1727), chief rabbi of the Ottoman Empire, writes: if the only other enablers are Jewish too, then the prohibition of Lifnei Iver is still violated.

But do we rule like the Dagul Mervavah who says that there is no rabbinic prohibition when the violator is willfully violating it? Rav Moshe Feinstein (IM YD I #72) rules that one can only rely upon this Dagul Mervavah in combination with another factor. The Mishnah Berurah (347:7) disagrees with the Dagul Mervavah.

ONAAS MAMMON ISSUE

We also find a concept in Halacha called Onaas Mamon. This concept, found in chapter 227 of the Choshain Mishpat section of the Shulchan Aruch, invalidates a sale when the price is either 16.7 % above or below the market value of the item. Landed properties would be excluded from this law, but it does apply both to movable properties as well intangibles.

The halachic authorities debate as to whether the law is applicable when there exists a range of prices and no set market value (See Bais Yoseph CM 209 who says there is no Onaah in such cases while the Bach and Shach state that there is, nonetheless). Rav Vosner zt”l in Shaivet HaLevi Vol. V #218 concludes that there is Onaah when there is no set price in the market, in accordance with the aforementioned Shach and Bach.

THE RULINGS

In regard to scenario number one, Rav Yitzchok Zilberstein in Vavei HaAmudim Vol. 63 #12 rules that the employee is not obligated to quit, although it may be meritorious to do so. Technically speaking, a storeowner has the right to establish any pricing system that he desires to – unless there is a set market price for the item.

Scenario number has to do with lying and more. In regard to the verse (Shmos 23:7) in Parshas Mishpatim of “midvar sheker tirchak – stay away from a false matter,” there is actually a three way debate as to how we understand this pasuk. The Chofetz Chaim rules in his Ahavas Chessed that there is an out and out prohibition to lie. This is in accordance with the view of some Rishonim. Other Rishonim hold that the verse is merely good advice, but not binding halacha. A third opinion holds that the biblical prohibition is limited to the parameters of the verse under discussion and is applicable to judges adjudicating law. Generally speaking, the view of the Chofetz Chaim is normative halacha.

Now while some authorities will give dispensation under pressing circumstances to follow the other view, here, in regard to scenario number two, a lie is being used to elicit money unfairly from the wealthy parent. The line has been crossed to actual theft.

The secretary can tell the boss that she will not be party to a lie and that if he wishes to tell him this message he must do so himself. If she feels that she will be fired unless she conforms, then she can word it in such a way where she is not lying by saying, “He told me to tell you that there is no room.” She, however, may not further a lie that is used to illicitly take money from someone else.

It should be noted that the Shulchan Aruch rules that a gabbai tzedakah who takes tzedakah money from someone who cannot afford it and is just giving because he was guilted into doing so out of embarrassment is in violation of theft. The same would be true here, because the wealthy man is not donating to the school out of altruism but because he was cornered into doing so.

In regard to scenario number three, there really is no heter to remain in the job. It is a situation of absolute theft and one may not be party to such an activity.

The author can be reached at [email protected]

(YWN World Headquarters – NYC)

3 Responses

Been there. Three times. Quit twice, fired once. And all supposedly frum bosses. Medavar sheker tirchak.

and if the boss tells the secy to tell the person on the phone that he is not in, is she supposed to quit?

What about working for someone who does not pay the legally required minimum wages? What about working for someone who doesn’t pay his suppliers and makes his employees cover him from taking calls from the upset vendors?

I find it amazing that the frum community doesn’t pay much heed to employers who flagrantly break the law or are dishonest. One of the first questions a person is asked after 120 is if they were honest in business!