V’anisa v’amarta (26:5)

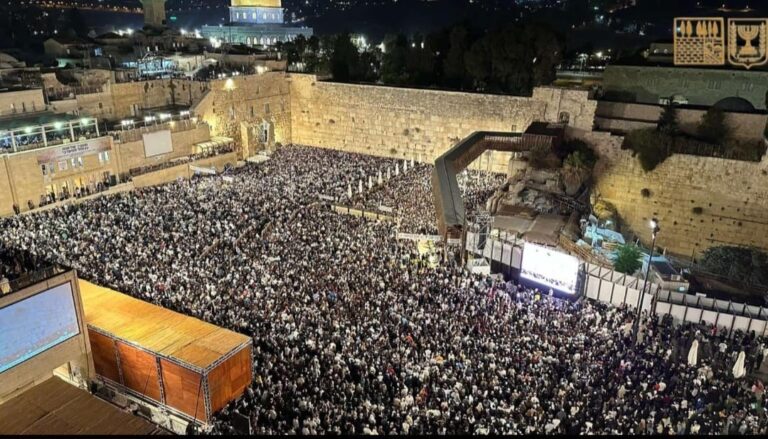

A farmer is required to bring bikkurim, the first ripened fruits of the seven species for which the land of Israel is praised, to the Beis HaMikdash. There he presents them to a Kohen as a sign of gratitude to Hashem for giving him a successful harvest. He then recites a declaration of appreciation for Hashem’s role in Jewish history. Rashi writes that this proclamation is made in a raised voice. Why does the Torah require the farmer to make this statement in a loud voice?

The following story will help us appreciate the answer to this question. Amuka, located in the north of Israel, is the burial place of the Talmudic sage Rebbi Yonason ben Uziel. Amuka is famous for its mystical ability to help those who are longing to get married find their matches, and people travel there from around the world to pray for a spouse.

Although it is common for people to pray in Amuka with an intensity emanating from personal pain, somebody was once surprised to see a married woman praying there with great happiness. In her response to the onlooker’s curiosity about this, she taught a beautiful lesson.

“I had a very difficult time with dating. Somebody finally suggested that I travel to Amuka, where I poured my heart out in prayer. Shortly thereafter, I was introduced to the man who is now my husband. I felt that if I came here to cry out from pain, it was only appropriate to return here to joyfully express my gratitude.”

The S’fas Emes explains that every person’s livelihood is dependent upon Hashem’s decree. Many times, this correlation is masked by events which make it appear that the person earned his income through his own creativity and perspiration. The farmer, on the other hand, has no difficulty recognizing that his financial situation is beyond his control and precariously rests in Hashem’s hands. As diligently as he plows and plants his land, he realizes that the success of each year’s crop depends upon the frequency and intensity of the rains, factors completely beyond his control. After putting in his own hard work, he prays fervently that the rains should come in the proper amounts and at the proper times.

When the farmer’s prayers are answered and he sees the first “fruits” of his labors, it would be easy for him to take credit for the successful harvest. The Torah requires him to bring his first fruits to the Temple as a reminder that his success comes from Hashem, and he must express the appropriate gratitude for His kindness. One might incorrectly assume that mumbling a quick “thank you” under his breath suffices to fulfill this obligation. The Torah therefore teaches that in expressing appreciation, lip service is insufficient. The feelings of gratitude must be conveyed with the identical intensity with which one initially prayed. Just as the farmer screamed out with his entire heart beseeching Hashem to bless him with a bountiful harvest, so too must he express his thanks with the identical raised voice.

So many times we cry out to Hashem from the depths of our hearts for a desperately-needed salvation – to bear children, to find our spouse, to recover from illness, or for a source of livelihood. When our prayers are answered and the salvation comes, let us remember the lesson of the first-fruits and loudly call out our thanks with the same intensity with which we prayed in our time of trouble.

V’anisa v’amarta (26:5)

A farmer is required to bring bikkurim, the first ripened fruits of the seven species for which the land of Israel is praised, to the Beis HaMikdash. There he presents them to a Kohen as a sign of gratitude to Hashem for giving him a successful harvest. He then recites a declaration of appreciation for Hashem’s role in Jewish history. Rashi writes that this proclamation is made in a raised voice. Why does the Torah require the farmer to make this statement in a loud voice?

The Chanukas HaTorah notes that the farmer bringing his first-fruits begins his review of national history by noting that an Aramean (Lavan) attempted to destroy my ancestor (Yaakov). Rashi explains that this was Lavan’s intention when he set out to pursue the fleeing Yaakov, but Hashem was aware of his malicious idea and warned him in a dream against pursuing his plan (Bereishis 31:23-24). Although Lavan was thwarted from executing his evil scheme, Hashem punishes non-Jews not only for their wicked deeds, but also for their thoughts.

The Gemora in Berachos (31a) derives from Chana’s prayer that one must pray quietly. The Gemora (Berachos 24b) explains that a person who prays loudly demonstrates a lack of faith in Hashem’s ability to recognize the intentions of his heart and to hear him if he whispers. Included in the declaration made by the farmer is a public confirmation that Hashem knows not only the words that a person speaks, but even the thoughts that run through his mind. By proclaiming Hashem’s knowledge of the unspoken, there is no longer any fear that the farmer will be viewed as questioning Hashem’s ability to hear us when we speak quietly, and he may therefore express his gratitude in an appropriately loud voice!

V’rau kol amei ha’aretz ki shem Hashem nikra alecha v’yaru mimeka (28:10)

There is a legal dispute (Shulchan Aruch Orach Chaim 31:2) regarding the wearing of tefillin on Chol HaMoed. Rav Yosef Karo writes that it is forbidden to wear tefillin on Chol HaMoed, while the Rema cites opinions that one is obligated to do so, adding that this was the prevalent custom in his region. The Paneiach Raza and the Maharshal bring a fascinating proof to support the latter opinion.

Moshe blessed the Jewish people that if they act properly and observe the commandments, the nations of the world will see that the name of Hashem is called upon them, and they will fear and revere them. The Gemora in Megillah (16b) understands the concept of the name of Hashem being called upon them as referring to tefillin. Tosefos (Berachos 6a) explains that the tefillin contain an allusion to “Sha-kai,” one of Hashem’s Divine names, with the “shin” represented by the letter “shin” that appears on the sides of the tefillin that is worn on one’s head.

The numerical value of “shin” is 300, which hints to the 300 days each year on which a person is obligated to wear tefillin. Subtracting the 52 Shabbosim on which a person is exempt from tefillin leaves 313 days. One is also exempt from wearing tefillin on four days of Pesach, two days of Shavuos, two days of Rosh Hashana, one day of Yom Kippur, and four days of Sukkos, for a total of 13. If a person doesn’t wear tefillin on Chol HaMoed, he will be left with too few remaining days. In other words, only if one wears tefillin every day of the year except for Shabbos and Yom Tov will he be left with a total of exactly 300 days to correspond to the “shin” on his tefillin.

Answers to the weekly Points to Ponder are now available!

To receive the full version with answers email the author at [email protected].

Parsha Points to Ponder (and sources which discuss them):

1) The section (26:1-11) detailing the laws governing bikkurim contains every letter in the Hebrew alphabet except for one. Which letter is missing, and why? (Baal HaTurim 26:4)

2) Moshe instructed the people (27:8) to write on stones all of the words of the Torah well-clarified. Rashi explains that “well-clarified” means that it should be written in all 70 languages, so that it may be easily read by anybody who wishes to do so. Why was it necessary to make the Torah accessible to the other nations of the world when the Gemora in Avodah Zara (2b) teaches that each of them was offered the Torah and refused to accept it? (Meged Yosef)

3) After the Jewish people initially accepted the Torah while standing near Mount Sinai, why were they required to reaccept it by standing on top of (27:11-26) Mount Gerizim and Mount Eival? (Peninim Vol. 6)

4) Rashi writes (29:12) that Moshe threatened the Jewish people with a total of 98 different curses if they fail to observe the commandments. Why did he specifically mention this number of punishments? (Tosefos Rid, Yad Av)

© 2011 by Oizer Alport.