A massive buildup of U.S. military assets across the Middle East is a message to Tehran: Washington now has the capacity to dismantle the core of Iran’s power structure with unprecedented speed, according to retired Vice Adm. Bob Harward.

In an interview with The Jerusalem Post, Harward, a former deputy commander of United States Central Command (CENTCOM), said the current posture reflects more than deterrence.

“One thing he’s illustrated is that President Donald Trump does what he says,” Harward said, pointing to Washington’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and its opposition to a nuclear-armed Tehran.

“Now he’s positioned the assets for a military action,” Harward added. “If he cannot meet the objectives regarding the nuclear and ballistic missile program, he’s willing to go beyond mediation and act.”

Harward outlined what he described as a carefully layered military strategy designed to neutralize Iran’s offensive capabilities while minimizing harm to civilians.

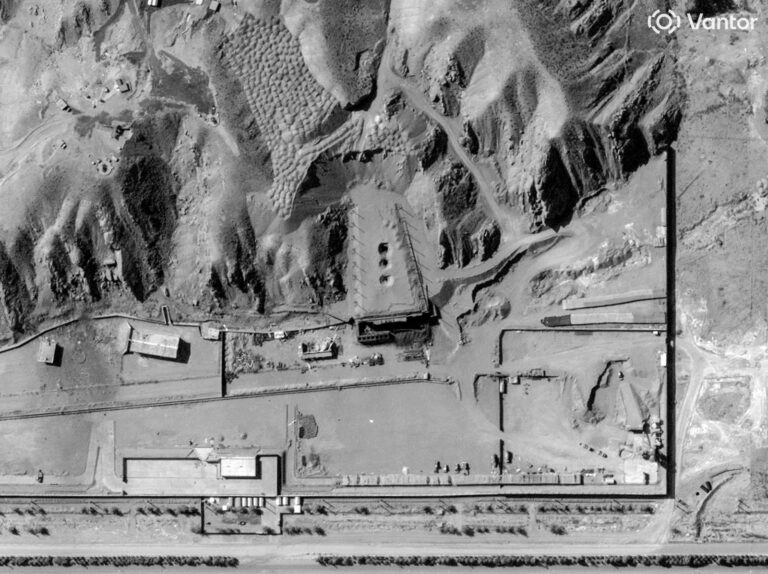

The first wave, he said, would focus on missile sites and launchers—assets that pose direct threats to U.S. forces and Israel. A second phase would target Iran-backed proxy groups outside the country, reducing the risk of retaliatory attacks.

Rather than targeting national infrastructure, a U.S. campaign would likely focus on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the powerful force that underpins the regime’s internal control.

“You’re not going to look at infrastructure,” Harward said. “This is to provide the Iranian people a change in government. It will be focused only on the things that enable the regime and the IRGC to suppress the people.”

Harward said that modern American warfare bears little resemblance to the campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, citing major advances in command, control, and targeting systems.

“Where previously you could do 40 or 50 strikes a day, we now have the ability to conduct hundreds of strikes a day,” he said. “That changes the equation completely for the regime.”

He argued that U.S. forces now possess the capability to decapitate Iran’s military leadership at extraordinary speed.

“If you’re targeting the IRGC and want to go after all their headquarters and facilities, you could probably do that in a matter of hours,” Harward said. “That’s unprecedented.”

Harward’s assessment is shaped in part by his personal connection to the country. His family lived in Iran from 1968 to 1979, and he was present shortly before the fall of the Shah during the Islamic Revolution.

He recalled that the decisive moment in 1979 came when Iran’s military shifted its loyalty from the monarchy to the public.

He believes a similar dynamic would be essential for any future political change.

“This is a regime that for 47 years has oppressed its people,” Harward said. “The bulk of them want change.”

Harward emphasized that any military campaign would need to align with the interests of the Iranian population, targeting the regime’s ability to communicate, intimidate, and suppress dissent.

The goal, he said, would be to weaken the ruling system without fueling popular resentment.

“This is about degrading their ability to control the people,” he said, “not punishing the people.”

Harward suggested that a potential U.S. strike on Iran would have implications far beyond the Middle East, offering a demonstration of American military power to rival nations.

“I don’t think anyone really understands the scale or capacity we have because no one’s ever seen it before,” he said.

“If it does happen, this will be illuminating for everyone—to understand where we’ve come in terms of size, scale, speed, and capacity, be it Russia or China.”

(YWN World Headquarters – NYC)