Iran’s government is preparing for rolling water cuts across Tehran as the capital faces its most severe drought in living memory, with rainfall levels plummeting to their lowest point in a century and reservoirs nearing collapse.

Officials warned Saturday that without immediate rainfall, parts of Tehran — home to more than 10 million people — could soon run out of water entirely.

“This will help avoid waste even though it may cause inconvenience,” Iran’s Energy Minister Abbas Ali Abadi said on state television, confirming the government’s plan to impose rationing and nighttime water cuts.

President Masoud Pezeshkian issued an even grimmer warning Friday: if the skies do not open soon, Tehran could face forced evacuation. “If it doesn’t rain in Tehran by late November, we’ll have to ration water. And if it still doesn’t rain, we’ll have to evacuate Tehran,” he said. He offered no details on how such an enormous operation would unfold.

Tehran, which sprawls along the parched slopes of the Alborz Mountains, typically relies on autumn rains and winter snowmelt to replenish its reservoirs. But this year, not a drop has fallen.

The Amir Kabir dam on the Karaj River, one of the five major reservoirs serving the capital, now holds just 14 million cubic meters of water — a fraction of the 86 million it contained at this time last year. The supply could sustain the capital’s needs for less than two weeks, warned Behzad Parsa, director general of the Tehran Water Company.

Across Iran, the situation is similarly dire. State television aired footage Saturday showing depleted reservoirs near Isfahan and Tabriz, while officials in Mashhad, the country’s second-largest city, confirmed they were weighing nighttime water cuts.

Earlier this summer, Tehran endured widespread power outages during a punishing heatwave, prompting authorities to declare two public holidays to conserve energy and water.

Iran’s water crisis has exposed the fragility of its infrastructure and deep-rooted policy failures. The country’s power grid, heavily dependent on hydropower and aging fossil-fuel plants, has been battered by dwindling water reserves and soaring demand.

Experts say the problem is not just nature — but decades of mismanagement. “We built water-intensive industries in the driest parts of the country,” said lawmaker Reza Sepahvand, citing steel and cement factories that diverted rivers away from populated regions. “Those industries should have been on the coast where desalinated water could be used.”

Iran’s National Water and Spatial Planning Organization has called for relocating such industries to coastal zones to reduce inland water stress.

Meanwhile, agriculture continues to consume around 80 percent of the nation’s freshwater, much of it through inefficient flood irrigation systems for crops unsuited to Iran’s arid climate. “We must modernize,” warned Agriculture Ministry official Gholamreza Gol Mohammadi, noting that outdated irrigation is depleting aquifers and straining power grids as pumps run dry.

Beyond the taps, the crisis has left visible scars across the Iranian landscape. Once-thriving rivers have turned to dust channels, and Lake Urmia — once one of the largest saltwater lakes on Earth — has almost completely vanished, leaving behind vast salt flats that generate suffocating dust storms.

Those storms now routinely blanket major cities, choking residents and worsening air pollution. Environmentalists fear Tehran could face similar conditions if the drought continues and its reservoirs fail.

The government’s plan to implement rolling water cuts may stave off the worst for now — but officials privately admit that without major policy shifts, Iran’s water crisis could become a national catastrophe.

(YWN World Headquarters – NYC)

6 Responses

The Iranian government will continue investing most of its money into trying to destroy Israel rather than into saving its own people.

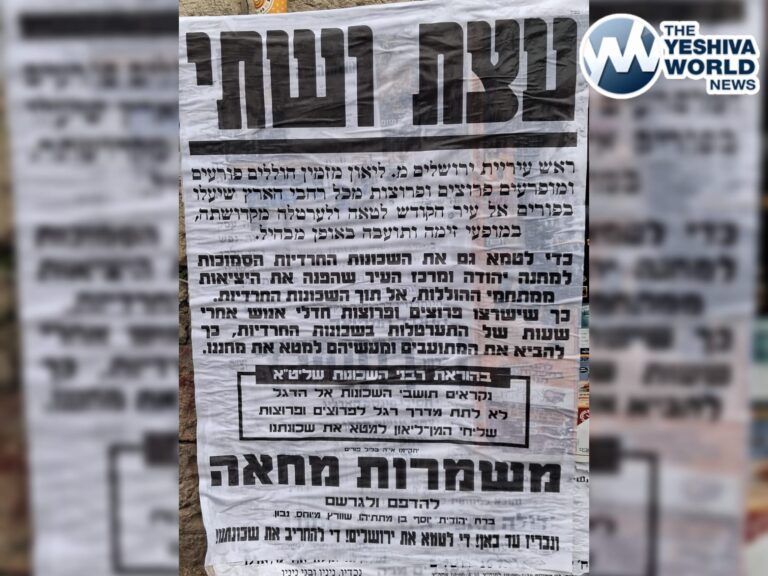

Yet more evidence that the Jews control the weather.

Just wait till they activate them space lasers….

כן יאבדו כל אויביך השם

It’s almost as though they should’ve spent more more time and money, researching and building desalination plans then they spent researching in building nuclear plants.

This is not a new problem. This crisis has been developing over the course of decades. Iran has drained their aquifers so fully that certain cities like Tehran are now literally sinking into the ground.

Iranians must rise up and retake control of their country from the brutal dictator who is subverting their will.

A big problem is that there is no leader currently poised to do that

They forgot tefillas geshem

When my kids ask why they have to take so many weather control classes in yeshiva, I tell them, “One day, you will see. It will be so important for us as Jews to control the weather. Learn mishna during lunch. Focus on your weather control.”

Now, they finally see! We did our part! My son moved a cloud from Isfahan to Tzsfat!

Yeshiva education – It all pays off in the end.