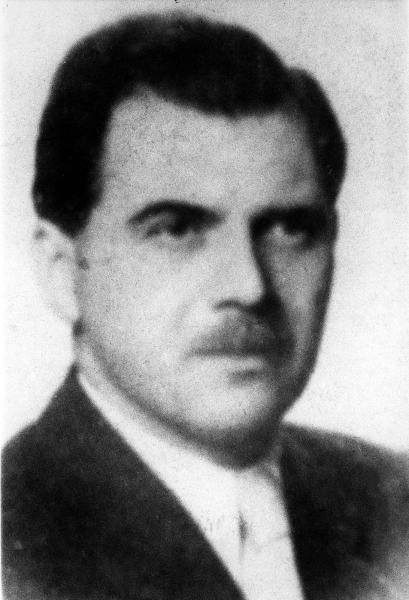

Newly unsealed intelligence files released by Argentine President Javier Milei have exposed how Josef Mengele Yemach Sehemam— Auschwitz’s “Angel of Death” and one of history’s most reviled Nazi war criminals — lived freely and comfortably in Argentina for nearly a decade after World War II. The documents paint a damning picture of a government that knew who he was, tracked him extensively, and still failed to act.

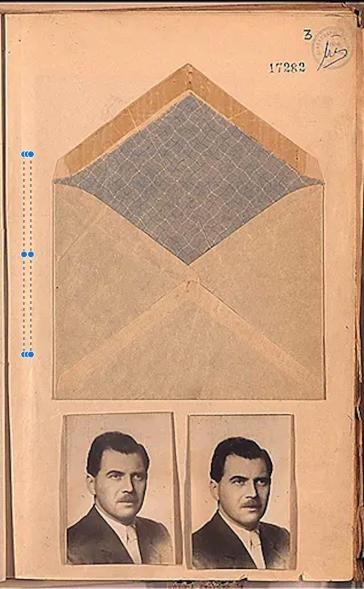

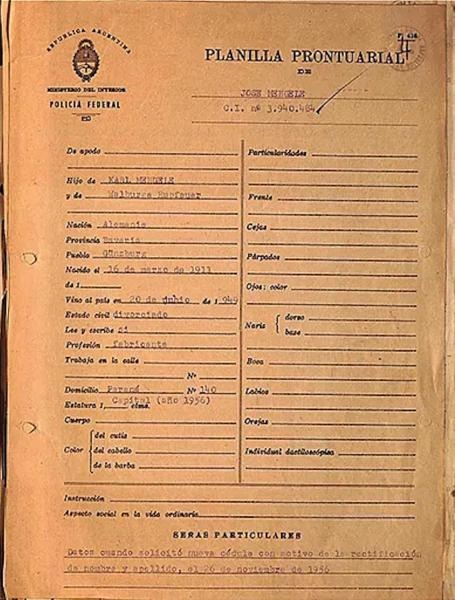

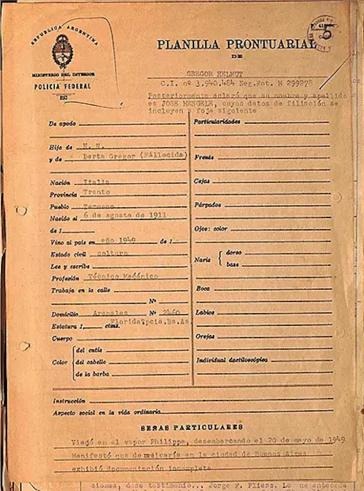

Mengele, infamous for his sadistic medical experiments on prisoners — especially twins — arrived in Argentina in 1949 using an Italian passport under the false name “Helmut Gregor.” By 1950, he had successfully obtained an Argentine immigrant ID card using that alias. The newly declassified files make clear that within a few years, Argentine authorities had identified him under his real name and possessed an extensive record of his activities, movements, and associates.

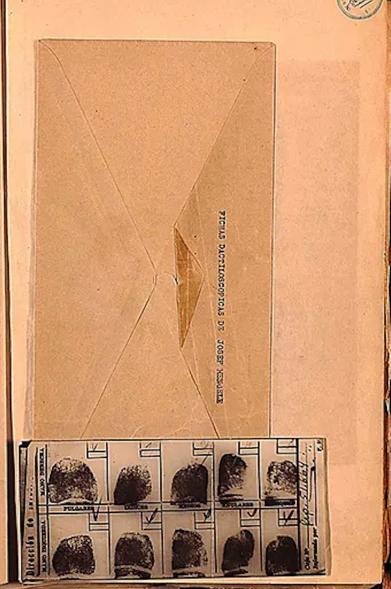

The archive contains photographs, intelligence reports, immigration documents, surveillance memos, foreign correspondence, and detailed investigative summaries. Together they show that by the mid-1950s, Argentina’s intelligence services knew not only that Mengele was in the country but also where he lived, the businesses he operated, the people he socialized with, and the details of his personal life. Officials documented that he had married his brother’s widow and was raising their son in Buenos Aires, and they were aware of financial support he received from his father, who reportedly traveled to Argentina to assist with a medical laboratory venture.

Eyewitness accounts included in the files — among them a chilling interview with Auschwitz survivor José Furmanski, an Argentine citizen born in Poland — describe in vivid detail the barbarity of Mengele’s crimes. Furmanski recalled seeing Mengele “many times in the Auschwitz camp,” identifiable by his SS colonel’s uniform and white doctor’s coat. As a twin, Furmanski provided harrowing testimony about Mengele’s experiments, calling him a “pathological sadist” who “gathered twins of all ages in the camp and subjected them to experiments that always ended in death.” His account describes scenes of mothers and children forcibly separated and sent to their deaths. The presence of this testimony in Argentine files leaves little doubt that the authorities knew precisely who Mengele was.

Despite this, internal documents show a pattern of bureaucratic dysfunction, miscommunication between agencies, political reluctance, and strategic indifference. Different branches of Argentine intelligence and law enforcement compiled meticulous files but often failed to share them, leaving crucial information scattered across agencies. Decisions on whether to pursue or ignore tips about Mengele’s location were handled inconsistently, sometimes only after press leaks or international pressure forced internal discussions — by which time it was too late to act.

In one of the most astonishing revelations, Mengele successfully petitioned in 1956 to have his Argentine identification documents corrected to reflect his real name. He did so using a legalized copy of his original birth certificate obtained from the West German Embassy in Buenos Aires. His ability to openly reclaim his identity years after the war underscores how secure he felt living in Argentina. Authorities recorded that he candidly discussed his SS past during this process, offering explanations for initially hiding his identity and acknowledging his role as a physician “in the German SS.”

By 1959, West Germany issued a formal request for Mengele’s arrest and extradition. Astonishingly, an Argentine judge rejected the request, dismissing it as an act of “political persecution.” The files show no evidence of further efforts to detain him. Instead, a secret memo dated July 12, 1960 — already months too late — directed officials to search for Mengele and investigate his business interests. By then, he had vanished. Under mounting international pressure, Argentina belatedly realized that Mengele had already fled to Paraguay, where he was shielded by the dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner, who shared Bavarian roots with him.

From Paraguay, Mengele eventually slipped into Brazil. The Argentine files track this escape largely through press reports and foreign intelligence provided by U.S., British, and Brazilian sources. They indicate that he was sheltered by German-Brazilian farmers sympathetic to Nazism, moving between isolated rural properties in São Paulo state throughout the 1960s and 1970s. He used multiple aliases, including “Peter Hochbichler,” and sometimes variants of his real name translated into Portuguese.

Mengele ultimately died in 1979 after suffering a stroke while swimming off the coast of Bertioga, Brazil. He was buried under the false name Wolfgang Gerhardt. His remains were exhumed and identified in 1985, and DNA testing in 1992 confirmed the match.

Nearly 80 years after the liberation of Auschwitz, the newly revealed archive delivers a stark and unsettling truth: Josef Mengele escaped justice not because he could not be found, but because those who found him chose not to intervene.

(YWN World Headquarters – NYC)

One Response

Argentina 🇦🇷 deserved every ounce of aggravation that Margaret Thatcher 🇬🇧 bestowed upon them