Newly released Argentine government files are offering a blunt, sometimes embarrassing look at how one of the world’s most notorious safe harbors for Nazi fugitives struggled — and often failed — to track down the war criminals who slipped through its borders after World War II.

The documents, made public last year under President Javier Milei, detail Argentina’s halting, rumor-driven pursuit of Nazi officials who found refuge in the country during and after the collapse of the Third Reich. They show a state apparatus long aware that war criminals were living openly on its soil — and largely incapable, or unwilling, to do much about it.

The files underscore a broader reality historians have long argued: Argentina’s hunt for Nazis was defined less by intelligence work than by sensational press clippings, Cold War anxieties and bureaucratic paralysis.

Few cases illustrate that dysfunction more clearly than the decades-long, ultimately futile search for Martin Bormann, one of Adolf Hitler’s most powerful lieutenants.

Bormann, who served as Hitler’s private secretary and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery, wielded immense behind-the-scenes power. He controlled access to Hitler, shaped policy through paperwork and patronage, and was a central architect of the regime’s most virulently antisemitic programs, including the Aryanization of Jewish property.

He vanished during the fall of Berlin in May 1945 and was sentenced to death in absentia at the Nuremberg Trials. Almost immediately, speculation took hold that he had escaped Europe via the so-called ratlines — clandestine routes used by Nazi fugitives to reach South America, often with sympathetic help.

Argentina became a focal point of those rumors.

According to the newly released files, Bormann was among the very few Nazi figures Argentine authorities made a sustained effort to locate. But that effort was deeply flawed from the start. Leads were overwhelmingly derived from newspaper articles — Argentine, American, British and Brazilian — rather than from actionable intelligence.

Officials painstakingly compared aliases floated in tabloids with men living in Argentina, cross-referencing immigration records, police files and hearsay from German-language publications circulated within émigré communities suspected of harboring Nazi sympathizers.

What followed was a blizzard of memos between ministries, intelligence offices, customs authorities, federal police and provincial officials — often redundant, slow-moving and disconnected. Investigations were repeatedly launched, dropped and relaunched as fresh headlines appeared.

The result, the files show, was a system perpetually reacting to rumors rather than driving its own inquiries.

At times, Argentine authorities treated implausible leads with startling seriousness. The documents reveal officials entertaining reports that Bormann was hiding in the jungles of Peru, Colombia or Brazil. In one episode in 1972, an elderly German man in Colombia was detained as a possible Bormann, despite skepticism from famed Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal. The man was eventually cleared and released.

Behind the urgency was a lingering diplomatic trauma: Israel’s 1960 abduction of Adolf Eichmann from a Buenos Aires suburb by the Mossad. That operation, which exposed Argentina’s role as a Nazi refuge, left officials acutely sensitive to international embarrassment.

The hunt for Bormann became as much about protecting Argentina’s reputation as about justice.

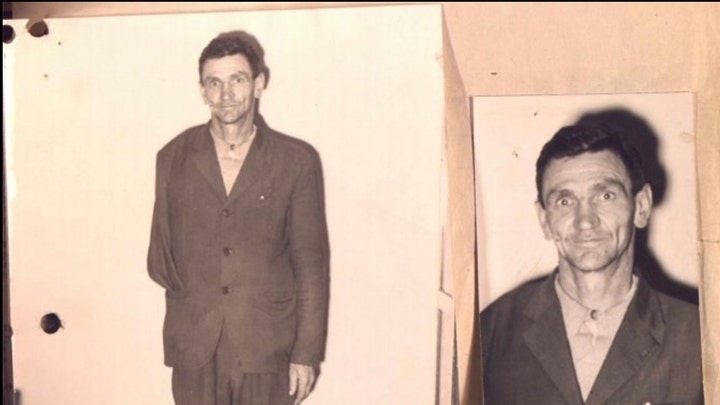

The most consequential misstep came in the late 1950s, when Argentine police zeroed in on a man named Walter Wilhelm Flegel. Based on fading testimony and rumors about an illegal German laborer, authorities convinced themselves Flegel might be Bormann in disguise.

The theory quickly unraveled. Flegel was missing an arm from an accident, had limited education, had lived openly in Argentina for years and bore no meaningful resemblance — biographical or physical — to Hitler’s former gatekeeper. Fingerprints didn’t match.

Still, it took authorities a full week after his 1960 arrest in Mendoza to accept the obvious and release him.

Even then, the rumors persisted.

The Argentine files ultimately close on a quiet anticlimax. In 1972, human remains discovered in Berlin were identified as Bormann’s through dental records. DNA testing in the 1990s confirmed the finding, establishing that Bormann had died during the fall of the German capital in 1945, never having set foot in South America at all.

By then, Argentina’s decades-long chase had already become a case study in how not to pursue war criminals: a hunt shaped by media frenzy, bureaucratic inertia and Cold War politics, rather than disciplined intelligence work.

(YWN World Headquarters – NYC)