By Rabbi Yair Hoffman for 5tjt.com

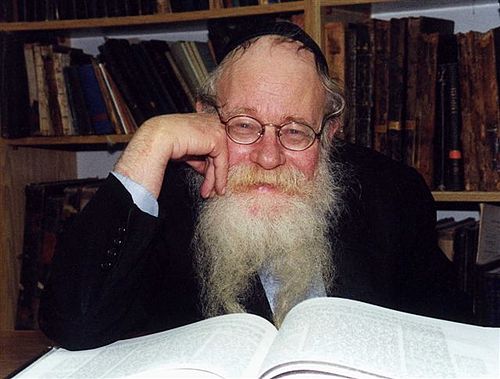

He was a descendant of one of the leading Chassidic Rabbis of the 19th century, Rav Avrohom Weinberg – the first Slonimer Rebbe. He was a trail-blazing translator of the Talmud. An author of numerous books. A recipient of the prestigious Israel Prize in 1988. Himself a Baal Teshuvah, he became a Rabbi who was interested in bringing Klal Yisroel back to their birthright of Sinai. By and large – he was fabulously successful. Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz z”l had had a profound impact on Jewish life and Judaism.

Rabbi Steinsaltz passed away last week in Shaarei Zedek Medical Center, at the age of 83, after battling with pneumonia. He was buried on Har haZeisim and eulogized in the press by both the Prime Minister and the president of Israel. He was humble and brilliant, and also mourned by numerous segments of Israeli society.

He was also, perhaps, the only person in the world who faced criticism from both the Pope’s favorite Reform Movement Affiliated Rabbi (ordained, however, at JTS), Jacob Neusner, and l’havdil one of the leading Torah figures in the Chareidi world – Rav Eliezer Menachem Shach zt”l.

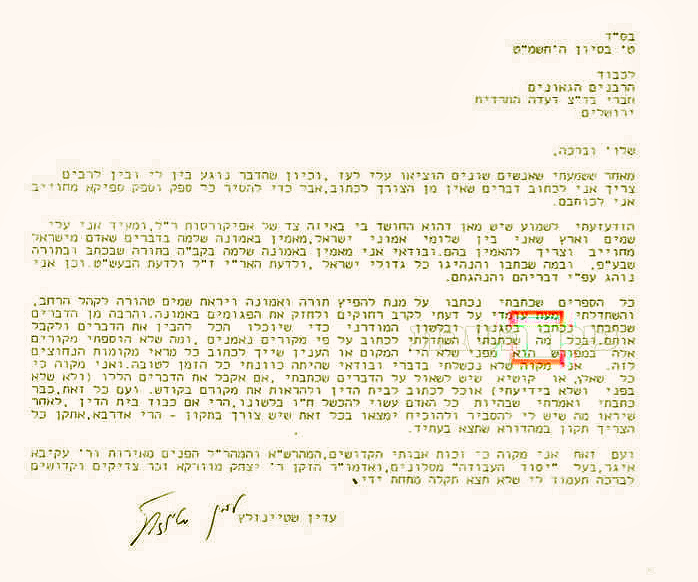

Rabbi Steinsaltz was best known for translating the Talmud into an easy to understand modern Hebrew. The translation did much more. It provided biographical sketches of each of the Tannaim and Amoraim mentioned in the Gemorah. It provided details as to the animals and fauna mentioned there too, and provided modern scientific takes on many of the concepts discussed in the Talmud. In 1983, on the 7th of Iyar, Rav Moshe Feinstein zt”l gave a haskama to the Gemorah, naming Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz. But, if one carefully looked at the text of Rav Feinstein’s letter, it is clear that he did not review all aspects of the Steinsaltz Gemorah. Some of the explanations went against traditional understandings of the text. The Talmud tells us that a woman cannot get pregnant immediately subsequent to the first instance of intimacy. Medical opinion thinks otherwise and Rabbi Steinsaltz comes up with a psychological explanation. That is just one example. There are many more.

The translation project took him 45 years, and Rabbi Steinsaltz began it in 1965. The translation was not just into an easy-flowing Hebrew. It was translated into English, French, Russian, and Spanish. The nikud vowelization was also key. It was such a good work that Artscroll itself is said to have used it as the basis of the nikud for their own Schottenstein translations. After 2010, he began and completed other translations too.

He was bold in his translations as well. There is a blessing that is recited when seeing 600,000 non-Jews mentioned in Brachos 58a – but what type of non-Jews? Is it just idol-worshipping non-Jews or any type? Our texts have idol-worshipping ones. Rabbi Steinsaltz, based on the works of Rishonim prior to any censors, changed it to all gentiles in his edition of the Gemorah. Gedolei haPoskim that this author consulted with, agreed that this was the correct halacha.

What about the criticisms? Neusner’s critiques (published in 1998) were an attempt to climb on the coattails of a rising star in intellectual Israeli circles. Neusner was a frustrated academic who was trying to make himself relevant in a world that rejected him. He created four straw theories about Rabbi Steinsaltz, deftly combining statements out of context and thoughts that he never said, and attempted to disprove all four. Neusner then tries to counter Rabbi Steinsaltz’s “alleged” theories and states that the Talmud is, in fact, carefully and systematically ordered, quite cogent, and an ordered system and structured coherently. Neusner had done this before to numerous others who had worked years on various translations of texts, only to discover that Neusner would hijack these translations and come out with his “own” translation albeit with a different numbering system and a critique of the former’s translation. They all complained. But Rabbi Steinsaltz did not. His humility did not allow him to do so.

Neusner’s attack on Rabbi Steinsaltz was a disingenuous lie. Rabbi Steinsaltz was the king of delineating and unfolding inner order. His explanations were known for their clarity. It is no wonder that academic journals quoted his translations and explanations.

Rav Shach’s animadversions expressed in 1989, on the other hand, were concerned with maintaining a different type of order. He felt that Rabbi Steinsaltz’s writings represented a danger to the system of the traditional Lithuanian style Yeshivah, in general, and to the traditional method of learning – specifically. It all began with a book published by Rabbi Steinsaltz entitled “Dmuyot Min HaMikrah – Biblical Images” (1980),which Rabbi Steinsaltz had intended to use as a kiruv tool – to bring the masses of Israeli society back to a respect for and deeper understanding of the biblical personalities who appear in Tanach.

The problem was that the book ascribed baser motivations to many of the Torah personalities that both the Talmud and the great baalei Mussar and Roshei yeshiva held dear. Rav Shach felt that it was both ill-conceived and disastrous. Worse yet, it had a potential to undermine everything that the yeshiva world held dear. Rav Shach had learned in the great Slabodka Yeshiva outside of Kovno under the Alter. Indeed, he was the very last person to leave the Yeshiva at the onset of World War One. Later, he learned in Kletzk. How could Bnei Torah be exposed to someone who expressed ideas that reflected a dim view of the heroic Torah personalities? The great Mussar personalities and Roshei Yeshiva who had vouchsafed Torah for the current generation – were brought up with the Mesorah known as Dakei Dakos – that the subtle sins of the great Torah personalities were not just subtle – but were near infinitesimal.

True, an appeal to the intellectual elite of Israeli society was necessary – but not at the expense of changing or altering our traditions of Torah. The book was based upon a series of lectures Rabbi Steinsaltz had given to non-observant soldiers serving in the IDF. Lehavdil, a similar event happened earlier in Jewish history. As Professor Louis Feldman z”l, the dean of Josephan scholars deftly pointed out in numerous articles – Josephus did the same thing when writing about the personalities in TaNaCh to a Roman audience. He made subtle changes to Yoseph HaTzaddik and Moshe Rabbeinu to make them likable heroes in the eyes of Romans. Josephus having attributed Elvis-like qualities to the personalities in TaNach for the Romans – did make Romans relate more to and appreciate the heroes of Klal Yisroel more. But it is absolute anathema to Bnei Torah. Lehavdil, Rabbi Steinsaltz in his book “Dmuyot min HaMikrah” made them more palatable to secular Israeli soldiers.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe, also a recipient of attacks from Rav Shach, stood by Rabbi Steinsaltz. Rav Steinsaltz had become observant through the work of Lubavitch teachers and became an espouser of Lubavitch philosophy. In 1960, a 23 year old Adin Steinsaltz wrote to the Lubavitcher Rebbe that he was currently teaching in a few Yeshivos in the Negev. The Rebbe wrote back to him asking for more information. It was not the first exchange of letters. Rabbi Steinsaltz was an adherent of the Rebbe and one of his most devout Chassidim.

Other Lithuanian Gedolim joined in with Rav Shach, including Rav Elyashiv. Eventually, he retracted the statements that were in this work and other statements – explaining that he did not have the opportunities that others had in being exposed to the true Mesorah. Admitting such a thing is a mark of greatness.

He wrote a number of outstanding works – the Thirteen Petalled Rose, On Teshuvah, and commentaries on Tanach too.

Rav Steinsaltz started Yeshivas that educated thousands and thousands of Jews – even one in Moscow. He also completed a nine volume work on the Tanya that explained the words of the Alter Rebbe of Chabad with unprecedented clarity. He was so active, so prolific, and so influential, that it will take some times to gauge his true impact on contemporary Judaism.

What about his family? Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz was born in Yerushalayim. According to a letter that Rabbi Steinsaltz had written his father was a direct descendant of Rav Avrohom Weinberg the first Slonimer Rebbe.

[While we are discussing the first Slonimer Rebbe, here is a tidbit that is unknown in the internal history of Slonim. The Slonimer Rebbe believed that some terrible tragedy was going to happen to European Jewry and he sent his grandchildren and others to fortify the Jewish Yishuv in Eretz Yisroel. The current Slonimer Chassidus (both the Black and White) stem from that decision. What is not known is that the Slonimer Rebbe himself used to fund raise for this Yishuv, but very early in his Chassidus – someone had malshined upon him to the Tsarist authorities as raising funds for use in another country was illegal. He was arrested and held to be taken away. Boruch Hashem, some quick thinking on the part of a resident of the Kaminetz community saved him. Were it not for that quick-thinking [bribery] we would never have Slonimer chassidus, no Sukkas Dovid on Shas, No Nesivos Shalom, and no Yeshiva Darchei Torah as it is now – Rabbi Yaakov Bender was a talmid of Rav Dovid Kviat zt”l – And, perhaps, no Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz – but we digress..]

There are rumors that he studied at Slonim and other rumors that his father had studied under the Chofetz Chaim in Radin. Somehow, someway, he had lost his way and went completely off the derech. He became a communist who fought against the fascists in Spain, and also was a member of the Stern Gang. Yet when young Adin was but eleven years old, his father hired a tutor – remarking, “I want you to be an Apikores, not an Am HaAretz.” His mother, adamantly refused to light Shabbos candles. His mother had her mother stay with them too. Her mother was observant, and Adin’s mother was very respectful. His father started a left wing newspaper.

Young Adin immersed himself in Torah study and never stopped. He also immersed himself in the writings and theology of Kotzk and also Chabad theology – even becoming its spokesman. True, he also pursued a strong secular education, but he used that reinforce and augment his Torah studies. His explanations of the Tanya have been well-received in Chabad circles and beyond.

Throughout the years, Rabbi Steinsaltz has managed to cultivate relationships with scientists, doctors and top politicians. He studied regularly with PM Levi Eshkol, PM Menachem Begin, PM Binyomin Netanyahu, mayors, and MK’s. He influenced them significantly bringing them closer to true Torah perspectives. Yehei zichro boruch.

The author can be reached at [email protected]

8 Responses

Thank you for the essay.

A few comments:

It might also be emphasized that Rav Steinsaltz’s work on the Talmud was not only a translation with interesting side notes, but a flowing commentary with an explanation weaved in. It was revolutionary for the time and the conceptual basis for Artscroll and all the other gemaros mevu’aros used today, which, whether they are in hebrew or English or French, are practically the STANDARD for ba’alei battim doing independent learning. Again, Rav Shteinsaltz is single-handedly responsible, publishing his gemaros, with no funding and without connections to any institutions. Anyone using a gemara of this type has Rav Shteinsaltz to thank (although his contribution has never been acknowledged by subsequent publishers, nor at the siyum haShas). I personally recall how the issuance of these gemaros caused an explosion in gemara learning by ba’alei battim who had beforehand not attended gemara shiurim and the gemaros being used not only by the participants but by the maggidei shiur themselves, including in Ger, which refused to go along with the ban on these gemoros, even after other Rabbonim had denounced them.)

Its concept was SO revolutionary that when Artscroll was about to publish its first volume, Masseches Makos, Rav Shach was intending to ban Artscroll as well. The agreement to NOT ban it was that Artscroll would have a translation ONLY and would NOT summarize the opinions of Rishonim and Acharonim, as Rav Shach thought that any summaries would destroy the yeshiva way of needing to understand RIshonim and Acharonim on one’s own. This is why Artscroll’s original version of Massechess Makos only had very brief summaries, nothing like what appears in the volumes that followed. (It was since been revised.) Today, those Rishonim summaries are, if anything, expanding, and Artscroll, Mesivta, etc no longer being controversial.

Another point is that the two English “translations” of Rabbi Shteinsaltz’s hebrew talmud are actually not translations, but original works loosely based on the hebrew original.

A carefully worded and almost accurate presentation. Kudos to Rav Hoffman for walking between the drops when writing about a great man who was criticized by the Lithuanian-trained Gedolim.

A few points struck me.

Using the term “Elvis-like qualities” is unbecoming and I hope regretted in hindsight. Clever, but inappropriate.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe was not simply “also a recipient of attacks from Rav Shach”. A review of history will show periods of non-stop virulent attacks on the Rebbe, mostly in the Yated newspaper, well-known to be the official disseminator of Rav Schach’s “hashkafah t’horah”. Rav Steinzaltz experienced collateral damage, but the real target was the entire Chabad movement.

Those who are well-versed in these controversies know that Rav Elyashiv was often coerced or misled into signing various attacks on those who were disapproved of in the Litvishe system. Rav Elyashiv himself, having been a dayan in the Zionist system and a great admirer of Rav Kook (his mesader kiddushin) knew better than to initiate vicious attacks on others, including the Rebbe.

But overall, very well done. Rav Steinzaltz’s legacy is found in almost every Torah home, often hidden, but still present.

I enjoyed reading your informative article. Just 2 points: (1) You state: “It all began with a book published by Rabbi Steinsaltz entitled “Dmuyot Min HaMikrah – Biblical Images”–however Rav Shach zt”l had an issue with the Gemorah itself, since the translation described the tannaim and amoraim like Steinsaltz’s friends and were not given the proper respect; and the concept of diluting the study of talmud which requires toil was lacking destroyed by the translation.

(2) It is wrong to describe Rav Shach’s zt”l remarks as “attacks” which has. derogatory tone to it–Rav Shach zt”l did not “attack” but lshem shemayim banned his seforim/Steinsaltz for the reasons set forth above, and there is no connection that Steinsaltz was a chabbad chossid, which is insinuated in the article.

Kol tuv

I thought that one of the problems was the fact that he changed the tzuas hadaf

rational–I am protesting the tone and substance of your words about Rav Shach. You should be very careful how you talk about Rav Shach who was THE Gadol Hador in his time. Anyone who disparages a Gadol or even a talmid chochom deserves niduy.

Also, it is demeaning to state that Rav Elyashiv was forced to sign his name for a cause. Heed my words and save yourself from punishment.

Kol Tuv

lshem shemayim :

Given that you’re ‘shem shomayim, I assume you’d want to get your facts straight, so here are a few:

1) You wrote that “the translation described the tannaim and amoraim like Steinsaltz’s friends and were not given the proper respect.” And that Rav Shach banned it because of this. I am not aware of Rav Schach’s having found such things in the gemaros, nor of his having said this. The STeinsaltz Hebrew is something like 75 volumes. In my extensive use of it, I have never seen anything such as what you describe. WOuld you be so kind as to cite examples, from the gemara? ANd anywhere in Rav Schach’s writings that point to such examples or state thhat he knows of such things?

2) As regards to the second point, that it would water down gemara learning, were you aware that Rav Schach had the same objection to Artscroll and was about to ban it? He only refrained from doing so due to Rav Gifter’s very active intervention? (That’s why Artscroll was so appreciative of Rav Gifter at their siyum celebration. He’s the only thing that came between them and their getting banned by Rav Schach.) I ronically, teh STeinsaltz gemara is closer to what Rav Schach wanted, as it does not contain comprehensive summaries of Rishonim, while Artscroll does. So, in fact, Artscroll was MORE objectionable to him (other than their having kept the tzuras hadaf.)

Lshem shemayim – Thank you for protesting the incredible chutzpa of “rational” in speaking the way he does about Maran HaRav Shach ztsl. it is clear that “rational” is a Lubavitcher and they have never forgiven Rav Shach ztsl for daring to speak up against their idol. It is their derech to attack and besmirch anyone who doesn’t agree with them.

BTW Harav Hagaon Rav Aharon Feldman shlitoh in his “The Eye of the Storm” chapter 17 masterly discusses the pros and cons of The Steinzaltz English Talmud. Again Lubavitchers besmirch him and his book as he also discusses, with his typical great courage, whether some Lubavitchers are heretics (chapter 22) and about “The Rebbe and Mashiach” (chapter 23)

To Imanonov, RAV Feldman’s thoughts critiquing the Steinsaltz English edition,which BTW is an original work that has no relation to the Hebrew version, first appeared in Tradition Magazine. A detailed response from its content editor and from someone who had been using it for years was published in a subsequent issue. I suggest you read those responses. Google it. The editor’s name was Rav Moshe Sober z”l. You can judge for your self whether Rav Feldmans response to the two letters was substantial and in point.