Georgia elections officials have no time to spare as they hustle to replace thousands of outdated voting machines statewide while fending off lawsuits in the wake of a much criticized gubernatorial election.

Even if the state manages to implement the $106 million purchase of new voting machines on schedule, some county officials worry the tight timeline could lead to another round of confusion as presidential politics drives high voter turnout.

“There is concern from my board and myself that we won’t have enough time to get our training in for ourselves, our poll workers and the voters,” Elections Supervisor Jennifer Doran of Morgan County said in an interview Wednesday.

Without proper training time, voters could face “confusion, anxiety” and longer waits as people learn to navigate the new system, Doran said.

The voting system overhaul comes after Republican Gov. Brian Kemp — previously Georgia’s top election official — beat Democrat Stacey Abrams for the governor’s mansion.

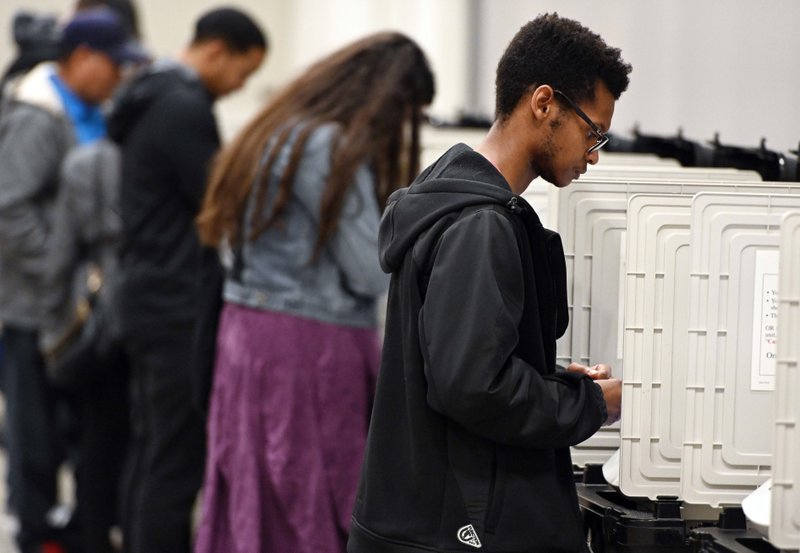

Myriad problems reported in that November 2018 election included hours-long wait times and malfunctioning voting equipment that prompted some voters to give up in frustration. Election security experts, meanwhile, warned that the electronic touchscreen machines Georgia has used since 2002 are vulnerable to hacking and don’t provide a paper record to audit and verify the result.

Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told The Associated Press that he’s got confidence in the new machines his office is buying, which will print a paper summary each voter can review before submitting the results for tabulation.

But cybersecurity experts say the new machines still have many of the same problems and vulnerabilities. Each paper summary will have a QR code above the results that will be machine-read, and voters will simply have to trust that the code reflects their choices. In the event of a recount or an audit, the printed choices on each paper summary will be counted by hand. But experts worry that voters might not take the time at the polls to verify their selections.

Raffensperger said the machines will be rigorously tested for accuracy before they’re used, and that he’d be open to working with the new vendor, Dominion Voting Systems, to move toward a system that removes the unreadable code in future election cycles.

Raffensperger meanwhile declined to discuss any backup plan, insisting that the new machines will “be in place” for next year’s March 24 presidential primaries.

Unlike many other states, Georgia law requires that all counties use a uniform voting system. That means that replacing outdated equipment can be a monumental task.

Under Raffensperger’s timeline, state and county election officials have less than eight months to follow through on the purchase of 30,000 electronic touchscreen voting machines and 3,500 ballot scanning devices for delivery to polling sites across 159 counties. They’ll need to be certified by the state, programmed and tested, and county election officials and poll workers need to be trained to use them.

“The timeline looks pretty tight for us to even start getting our first round of equipment and get training on it, much less fully implement it by March,” said Doran, whose elections challenges, in a midsize rural county east of Atlanta, are typical for Georgia.

The specter of a possibly rocky implementation has also worried critics suing to try to force the state to stop using the old voting machines, which they say are unsecure, hackable and can’t be audited.

Plaintiffs in that case expressed concern during a recent hearing that any implementation delays could leave Georgia voters stuck with the old machines for the 2020 presidential primaries and beyond. They asked U.S. District Judge Amy Totenberg to order an immediate switch to a system that uses optical scanners and hand-marked paper ballots, in part because they also plan to challenge the new machines in court.

Plaintiffs’ attorney Bruce Brown, who represents the Coalition for Good Governance, called the implementation schedule for the new machines “aggressive” during a hearing on those requests last month. Merritt Beaver, the chief information officer for the secretary of state’s office, didn’t dispute that characterization.

“It’s tight,” he said.

But David Becker, the executive director of the nonpartisan Center for Election Innovation & Research, who helped advise Raffensperger’s office on election security, says the timeline is feasible.

“Two months before an election, that is impossible. But eight months is very possible and particularly because the election that will occur in eight months is a presidential primary” where turnout will be lower than during a general election, Becker said.

“Eight months before a primary is probably just about right,” he said.

(AP)