Since breaking out of China, the coronavirus has breached the walls of the Vatican. It’s struck the Iranian holy city of Qom and contaminated a nursing home in Seattle.

And around the world, it’s carrying not just sickness and death but also the anxiety and paralysis that can smother economic growth.

From Florida, where the CEO of a toy maker who can’t get products from Chinese factories is preparing layoffs, to Hong Kong, where the palatial Jumbo Kingdom restaurant is closed, businesses are struggling. The virus has grounded a British airline, and it’s sunk a Japanese cruise-ship company.

The cumulative damage is mounting.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development this week slashed its forecast for global growth for this year to 2.4% from 2.9%. It warned that Japan and the 19 European countries that share the euro currency are in danger of recession. Italy may already be there.

Capital Economics expects the Chinese economy to shrink 2% in the January-March quarter and to grow as little as 2% for the year. That would be a disastrous and humiliating comedown for an economy that delivered a sizzling 9% average annual growth rate from 2000 through last year.

The bleak outlook and nagging uncertainties about how severe the damage will be have shaken financial markets. The Dow Jones industrial average, gyrating wildly from day to day, has plummeted nearly 12% over the past month.

“The virus is going to go on, and it’s going to impact a lot of countries and economies,” said Sondra Mansfield, who owners Chalk of the Town in New York City, which makes T-shirts and tote bags that children can write on with chalk.

With global supply chains disrupted by quarantines and travel restrictions, Mansfield worries about maintaining access to the supplies she needs — T shirts from India and Honduras and markers from Japan.

“I think it will get worse before it gets better,” she said.

When COVID-19 emerged in China a few weeks ago, many economists envisioned something like what happened when SARS hit China and Hong Kong in 2003: A short-lived interruption of Chinese economic growth, one that left the global economy largely unscathed.

Yet the new virus has spread far faster and more widely than expected. Between November 2002 and early August 2003, SARS infected 7,400 people in 32 countries and territories and killed 916. By contrast, COVID-19 has infected more than 100,000 people and killed more than 3,400 in 90 countries. And the toll is growing.

“This is not a China issue anymore,” said Jacob Kirkegaard, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

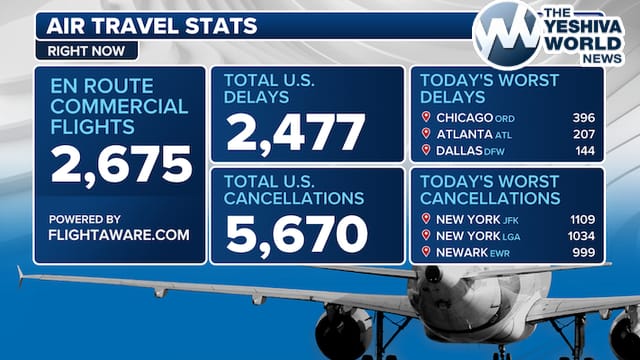

Business travel in the United States has slowed sharply in the face of the outbreak. Numerous large companies, including Amazon and Google, are restricting non-essential travel. The result is a dire financial blow for the travel and tourism industries — from airlines and hotels and restaurants to cruise ship companies and conference centers.

Some airlines, including United, have cut back on flights both within the United States and internationally. The industry, already reeling from the grounding of Boeing’s 737 Max, stands to be severely damaged by the viral outbreak, especially if travelers stay away for months to come.

In Europe, Germany’s largest airline, Lufthansa, says it will cut up to 50% of its flights in the next few weeks, having suffered a drastic drop in reservations. The struggling British airline Flybe collapsed last week as the outbreak quashed ticket sales. Air France and Scandinavian Airlines are freezing hiring and offering unpaid leave and shorter work hours as they endure a drop in passengers and cargo.

The pullback in air travel has led to the cancellations of high-profile conferences, from the Geneva auto show to a global health conference in Orlando, Florida, to South by Southwest, the annual festival of music, film and technology in Austin, Texas. Those cancellations, in turn, are dealing financial setbacks to the cities that normally host them and count on the financial windfalls they bring.

Amusement parks are being hurt by the sudden reluctance of people to travel and mingle with crowds. Disney’s Shanghai Disneyland and Hong Kong Disneyland remain closed. Other theme park companies, like Six Flags and SeaWorld Entertainment, will likely suffer, too.

As more people stay home, some small pockets of the U.S. economy could benefit, including food delivery outfits, video conference companies and entertainment streaming services. Most of corporate America, though, is vulnerable, and earnings growth is likely weakening. Oxford Economics, noting the “darkening outlook,” puts the odds of a U.S. recession at 40%.

Last week, the Federal Reserve announced a surprise half-point cut in its key interest rate to try to aid the economy in the face of the coronavirus. The Fed is expected to cut rates further in coming weeks, though economists question whether that will do much to bolster investor or consumer confidence. Central banks in Australia, Canada, China and Japan have also acted to support their economies. The European Central Bank is expected to announce its next steps this week.

The virus and the measures meant to contain it have choked the supply chains that companies around the world had come to rely on. Chinese authorities locked down Wuhan, the industrial hub at the center of the outbreak, as well as surrounding cities. Stranded by travel restrictions, millions of migrant factory workers who had returned to their home villages for the Lunar New Year couldn’t get back to work.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development said last week that a shortage of industrial parts from China, caused by the coronavirus outbreak, has triggered a “ripple effect” that sent exports from other countries tumbling last month.

The Yayuan Toy Factory, which makes plastic cars in the southeastern Chinese city of Yiwu, remains shut down. The factory’s 12 workers had gone to Shanxi province in western China and Guizhou in the southeast for the New Year holiday — and haven’t made it back.

Executives of Salus Brands, a company in Tempe, Arizona, that sells swimming-pool floats and bottles of slime, fear that deliveries from its Chinese factories won’t arrive in time for summer vacation.

“If we can’t get product in stores by Memorial Day week or shortly after, we lose our season,” said Dave Balkaran, the company president.

“Sadly, it’s the small and medium-sized enterprise that will get hurt the most and the soonest,” said Andrew Shoyer, a former U.S. trade official who is a partner at the law firm Sidley Austin. Larger companies, he noted, are more likely to have other suppliers to draw upon if some factories are disrupted.

Jay Foreman, CEO of the toy company Basic Fun in Boca Raton, Florida, said he is being forced to lay off 10% of his 175-person global staff. That’s because factories in China can’t deliver enough of his products, which include Tonka Toys and Care Bears. China’s factories are allocating most of their reduced production to giant toy companies and squeezing out the little players like him, Foreman said.

“I am getting vendors who are actually encouraging me to (make smaller) orders because they’re trying to spread out the capacity,” Foreman said. “I don’t want lower orders. I want higher orders.”

In Hong Kong, downtown streets that are usually jammed on weekdays are eerily empty and homeowners are unloading property at steep losses. Some hotels say they are 90% empty.

The virus is depressing tourism in South Korea and Japan, which have been severely hit by the outbreak. Fujimisou, a traditional Japanese inn in central Japan, had managed to fend off bankruptcy by catering to Chinese tour groups — until they stopped coming.

Also filing for bankruptcy was a famous maker of potato croquettes in Hokkaido and the Luminous Cruising Co. It was crushed by cancellations after an outbreak of virus cases aboard the Diamond Princess, a Carnival Corp. ship that was quarantined for weeks offshore from Yokohama.

(AP)