President Joe Biden’s push to have Congress replenish wartime aid for Ukraine as part of a deal on border and immigration policy changes will almost certainly drag into next year.

The Senate, which had postponed its holiday recess, returned to Washington on Monday after negotiators worked through the weekend on the border legislation, trying to reach an agreement that could unlock the Republican votes for Biden’s $110 billion package of aid for Ukraine, Israel and other security priorities.

But senators said they still had plenty of work ahead, and it remained uncertain how many more days the Senate will remain in session this week. Barely half of the senators returned for a Monday evening vote.

“Obviously we need time,” said Sen. Chris Murphy of Connecticut, the top Democratic negotiator.

The delay heaps more uncertainty on the future of the Biden administration’s priority of providing support against Russia’s invasion. It also puts a potential pause on politically fraught negotiations over immigration and border security policy, though Senate negotiators planned to continue working on the package.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer said the negotiations were “among the most difficult things we’ve done in recent memory.”

“Everyone knows that something should be done to fix our broken immigration system,” he said in a Senate floor speech to start the week. “But we can’t do so by compromising our values. Finding the middle ground is exceptionally hard.”

The House has already departed for the year as Congress settles into a long winter’s break. Lawmakers aren’t scheduled to return until the second week of January, and they will then need to tend to other matters besides the Ukraine funding, including facing a partial shutdown in mid-January if Congress can’t pass a government funding package.

But as the Senate undertook the first substantial rewrite of immigration and border security law in decades, Republicans insisted they would not agree to rushing legislation.

“Getting this agreement right and producing legislative text is going to require some time,” Republican Leader Mitch McConnell said on the Senate floor.

Schumer had scheduled additional work days this week in hopes of pushing the Ukraine aid through the chamber, but made no mention of a vote on the package on Monday. He said both Republicans and Democrats would need to make more concessions and it would take “some more time to get it done.”

Members of the core Senate negotiating group — Murphy and Sens. Kyrsten Sinema, an Arizona independent, and James Lankford, an Oklahoma Republican — met with White House staff on Monday and planned to continue meeting throughout the week.

“We’re all going to be back in January, but it’s going to take a while to be able to finish up all the text,” Lankford said.

The weeks-long wait comes as the Defense Department says it has nearly run out of available funds for supporting Ukraine’s defense. In a letter to Congress, the Pentagon notified lawmakers last week that will soon be transferring more than $1 billion to replenish stockpiles sent to Ukraine, with no further funds available as it maintains the United States’ own military readiness.

“Once these funds are obligated, the Department will have exhausted the funding available to us for security assistance to Ukraine,” according to the letter obtained by The Associated Press.

The department said “it is essential that Congress act without delay” on the pending supplemental request.

Ukrainian forces tried to launch a counteroffensive this year, but faced dug-in Russian troops, minefields and other hazards. They struggled to make any significant gains.

As the conflict grinds towards the end of a second year, U.S. public support has waned for sending billions of dollars more in weapons and economic aid. The European Union, too, had to push into the new year a plan to supply Ukraine with $54.5 billion after a veto from Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, a right-wing leader who is on good terms with Russian President Vladimir Putin as well as Donald Trump, the former president and front-runner for the Republican nomination next year.

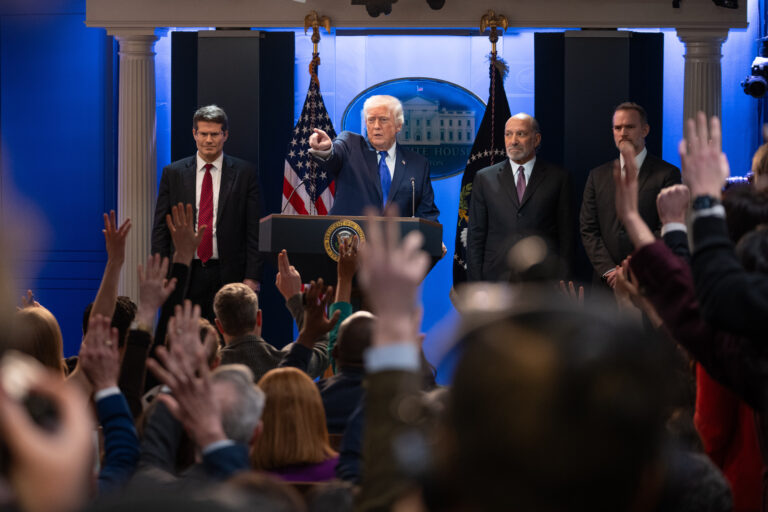

As his country scrapes low on money to repel Russia, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has traveled the world to ask for support. He elicited praise from Republicans after meeting with them in the Capitol last week, but the conservatives remained unmoved and in no hurry to approve Biden’s emergency funding request.

Republicans have said there is still time to redouble support before Ukraine’s defense suffers. Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa said that since the European Union put off sending Kyiv more money until the new year, he thinks the U.S. can as well.

“If it’s OK for them, it’s surely OK for us,” he said.

Dozens of Republican House members have signaled they won’t support continued Ukraine aid, and even GOP senators who in the past have been stalwart advocates of the Ukraine war effort have insisted that Congress also pass new border restrictions.

Biden has offered to compromise on border and immigration policy, and top White House officials have joined the Senate negotiations, including Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas.

Negotiators have closed in on a list of immigration enforcement measures, including detaining people who claim asylum at the border and granting nationwide authority to quickly remove migrants who have been in the U.S. for less than two years. They have also agreed on raising the initial threshold for people to enter an asylum claim in credible fear screenings.

The White House has tried to preserve an immigration program known as humanitarian parole. The Biden administration has leaned heavily on the use of humanitarian parole as part of its policy of providing legal pathways for some migrants to enter the country while beefing up consequences for those who don’t use those pathways. But Republicans have objected — and even sued to stop it — saying that the administration is essentially bypassing Congress and improperly letting migrants into the country who normally wouldn’t qualify.

Still, Biden’s willingness to make concessions in the negotiations has alarmed immigration advocates and drawn criticism from influential Hispanic Democrats.

On a conference call with reporters Monday, advocates decried the policies under consideration as a return to the strategies pursued by Trump that left large numbers of migrants waiting in Mexico to apply for asylum in the U.S.

“If you have asylum seekers pushed back into Mexico, it’s going to be extremely dangerous,” said Kerri Talbot, executive director of The Immigration Hub.

The senators have also described their work as a complex undertaking as they delve into laws that for years have been at the center of intense legal and political fights.

“As we get into the text, it’s really hard,” said Murphy, but he added, “I think as Ukraine’s peril becomes more serious and more immediate, the urgency to get this done will rise.”

(AP)