There are moments when you walk into a room and immediately realize that something important is happening—not because of what is announced, but because of what is felt.

That was the experience this year at Bell Works.

It was the annual Kinyan HaMasechta gathering—a night when working bnei Torah from across the world come together to celebrate a shared commitment: learning Gemara with consistency, structure, and relentless chazarah, not as inspiration alone, but as something owned.

From the moment people began arriving, the scale was unmistakable. Men streamed in steadily, purposefully, from every direction. This did not feel like a crowd gathering for a program. It felt like a family arriving for a reunion.

As the men came in, there was something else you couldn’t miss. Nearly everyone was holding a Gemara. Not tucked under an arm for show, but carried naturally—almost as if it were their entrance ticket. These were not pristine volumes. They were worn, bent, and softened from use. Margins filled with pencil markings, summaries squeezed between lines, notes layered upon notes—the unmistakable hallmarks of chazarah. You could tell at a glance who belonged. Before a word was spoken, the Gemaros themselves told the story. This was a room full of people who don’t just attend learning—they live with it.

Lining the space were rows of banners—faces of men learning together week after week in chaburos across the country and across the world. Familiar and unfamiliar at once. Further along, another set of banners quietly told a story of their own. What began in 2016 with eight chaburos had grown year after year—fourteen, then twenty-six, then thirty-two. Fifty-three. Seventy-eight. Over one hundred. One hundred forty-one. One hundred eighty-seven. Two hundred twenty-nine. And now, in 2026, two hundred eighty-two chaburos strong.

Each number represented something deeply personal: another group of men who decided that Torah would not be something admired from a distance, but something owned.

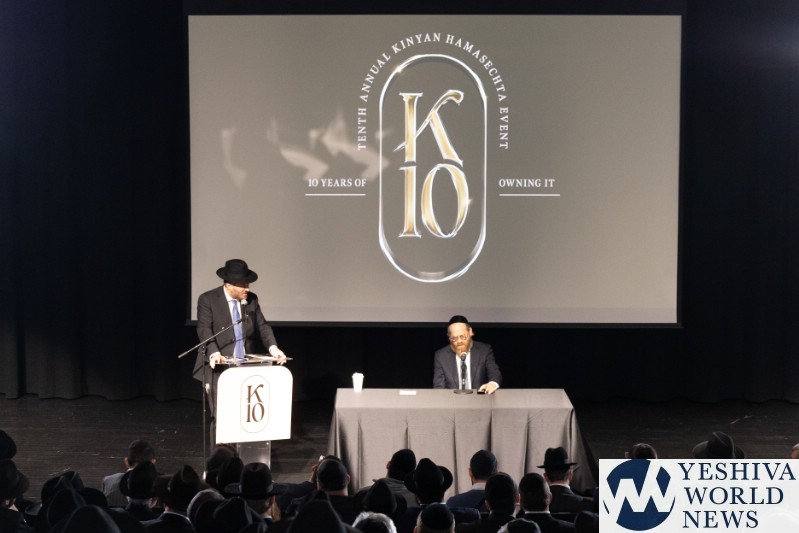

The event began with a thoughtful Q&A that set the tone for everything that followed. Moderated by Rabbi Pinchas Weinberger, the session was introduced as something deeply tied to the very essence of Kinyan. When a person becomes genuinely connected to his Gemara and his Torah through consistency and chazarah, Rabbi Weinberger explained, it reshapes the way he sees life itself. The Q&A was meant to help participants recognize and appreciate that new perspective. Rabbi Uri Deutsch addressed questions that sit at the intersection of Torah and lived reality: how to properly value the role of the working person, even when his day is not spent entirely in the beis medrash, where true hashkafah is formed—through a personal rebbi or through the pull of the latest podcast; how much influence parents truly have over their children versus the role of schools; and how present and involved a parent should be in a child’s inner world. These were not abstract discussions, but reflections of how Torah, when truly owned, begins to guide choices far beyond the beis medrash.

The event then flowed into a reception that made clear this was not merely a formal gathering. Conversations flowed easily, not as networking, but as connection. The Kinyan family found each other across the room, some seeing each other for the first time since last year’s gathering. New faces were welcomed naturally, drawn into the circle, introduced not as guests but as family. It felt less like mingling and more like coming home.

Then the doors opened for the retzufos seder.

Two enormous rooms filled, well over fifteen hundred men opening Gemaras almost in unison. Within moments, the kol Torah rose—full, focused, unmistakable. Not just loud in the sense of noise, but powerful in the sense of purpose. Men bent over the page, arguing, smiling, immersed. It rivaled any beis medrash in the country, not because of scale alone, but because of focus and sincerity.

When the seder ended and the siyum began, it was clear that this was not a celebration reserved just for those who had completed a masechta. It was a siyum for everyone in the room. Because a siyum is not only about completion; it is about commitment. And that commitment was visible everywhere you looked.

The dancing that followed had no edges. No observers standing on the sidelines. Songs that are sometimes aspirational felt deeply personal. Ashreinu and Mah Ahavti Torasecha were not about someone else. They were about us.

Only then did the event transition into the dinner.

It was there, in that setting, that the deeper layers of the night began to unfold.

Throughout the meal, participants shared reflections drawn from their own lives—quiet, honest, and remarkably consistent. Again and again, their words returned to the pillars that define Kinyan: clarity, chazarah, which brings to cheishek.

More than one spoke about the defining challenge of our generation: attention. Entire industries spend billions of dollars competing for it—because it is invaluable. And like anything valuable, when its owner does not recognize its worth, it is easily taken. One speaker compared it to a plot of land long assumed to be worthless—until a zoning change revealed its true potential. Overnight, offers poured in. The land itself had not changed; only the understanding of its value had. Our attention, he suggested, is no different. When we don’t recognize what it’s worth, we give it away freely. When we do, we guard it carefully—especially during learning. That guarding of attention, they explained, is what creates clarity.

Others spoke about the small but intentional choices that make that clarity possible: putting the phone away, protecting time, creating space for focus. Not as a rejection of the modern world, but as a way of engaging it more fully. When attention is whole, learning changes. It becomes sharper, sweeter, and more alive. That sweetness—the cheishek—was not something manufactured; it emerged naturally when learning was given the dignity of full presence.

Another recurring theme was chazarah, and the ownership it creates. Writing in the Gemara. Summarizing. Forcing oneself to process rather than passively listen. That simple discipline, many shared, transformed their learning. Torah stopped slipping away and started staying with them. A masechta was no longer something they passed through, but something they carried.

Still others spoke about consistency—not as an abstract ideal, but as a stabilizing force in a full life. Work, family, and Torah all demand time and energy. But when Torah has a fixed place—first thing in the morning, last thing at night—it anchors everything else. It doesn’t compete with responsibility; it gives it balance. Over time, that consistency deepens chazarah, sharpens clarity, and sustains cheishek.

It was in this atmosphere that R’ Yitzchok Wagner, the Nasi of Kinyan, addressed the room.

Marking ten years of Kinyan HaMasechta, he spoke not about milestones, but about identity. Ten years of limud haTorah. Ten years of growth. Ten years of demonstrating what levels in Torah are possible for bnei Torah who work. As he welcomed 87 communities from across the globe, he shifted the focus away from geography. Wherever a person comes from, whatever side of the mechitzah they stand on, every member of Kinyan represents Torah lived with sincerity and growth. Titles fade. What remains is connection.

He reframed a familiar teaching. The yetzer hara, he explained, no longer announces itself loudly. In our generation it often comes quietly—through distraction, wasted time, fractured focus, and constant anxiety. But the second half of Chazal’s message is what matters most: Torah was given as the tavlin. Not to remove challenges, but to give us the tools to live fully and meaningfully in their presence.

Torah becomes that tavlin only when it is owned. There is a difference between attending and playing, between listening and committing. Ownership comes through consistency, writing, and chazarah—through becoming the driver of one’s learning rather than a passenger.

Rabbi Newman, the founder of Kinyan spoke next. He shared a letter that captured, with extraordinary honesty, what Kinyan HaMasechta can mean in a person’s most vulnerable moments.

It spoke of deep personal pain and isolation, of days when even getting out of bed feels overwhelming. And it spoke of Torah—not as an escape, but as companionship. The structure and responsibility of Kinyan became the force that pulled the writer forward, not by denying the pain, but by ensuring he did not face it alone.

He described a moment when sugyos reviewed countless times suddenly became personal. Sitting in a hospital room during a moment of uncertainty, he found himself reviewing the tefillah of Chana—words poured out for a child. Those words were no longer history. The tears not written on the page were present in the room. That depth, the letter explained, can only come from Torah that has been reviewed, internalized, and lived.

The room listened quietly—not out of drama, but out of recognition.

This, perhaps more than anything, revealed the quiet greatness of Kinyan HaMasechta. It is not only about finishing masechtos. It is about allowing Torah to enter the most private spaces of a person’s life. When Abaye and Rava are no longer distant voices, but companions. When sugyos walk with a person through fear, hope, and tefillah. That is a true kinyan.

Following Rabbi Newmans remarks, the keynote address was delivered by Rabbi David Nakash, the driving force and original visionary behind Kinyan HaMasechta. Speaking with passion and unmistakable conviction, he invited the room to look back ten years—to remember not just how Kinyan began, but what it set out to change.

Ten years ago, he explained, Kinyan began as a dream. A dream that baalei batim could have serious learning. That the fire, sweetness, and inner joy of Torah were not reserved for the yeshiva world alone. The greatest obstacle was not time, or work, or ability—but belief. The deeply ingrained assumption that a working person could connect to Torah, but not truly taste it. That the gishmak, the depth, the fire, belonged to someone else.

That belief, R’ Nakash said, was the first thing Kinyan had to dismantle.

And now, ten years later, standing in a room filled with thousands of people who were clearly living that connection, he said it could be stated plainly: the landscape has changed. Forever. Baalei batim have formed a real, enduring connection to Torah. The fire does apply. The sweetness is accessible. And once that connection is made, it does not disappear.

R’ Nakash recalled the words spoken at the very launch of Kinyan HaMasechta, when Harav Efraim Wachsman addressed a small group gathered in Rabbi Newman’s home. This, Rabbi Wachsman said then, is not an initiative. It is not even a learning program. It is a life program. At the time, those words sounded aspirational. Standing here now, R’ Nakash noted, they sounded descriptive.

He then turned to a well-known Chazal: one who is accustomed to having a candle will merit children who are talmidei chachamim. What does a candle have to do with the next generation? R’ Nakash explained that in earlier times, the candle was what illuminated the home on Friday night. Fathers sat by its light, learning. Children watched. They absorbed not only the words of Torah, but the sight of Torah lived, valued, and loved. That image, repeated week after week, shaped the future.

That, R’ Nakash said, is what Kinyan was built to restore: homes where Torah is visibly present, consistently reviewed, and deeply cherished. Homes where children grow up seeing that Torah is not something left behind in youth, but something carried proudly into adulthood.

He then returned to another moment from the early days of Kinyan—words he described as almost prophetic. Imagine, Rabbi Wachsman had said, a time when a Jew could walk to a wedding and find baalei batim standing outside, immersed in Torah. R’ Nakash paused, then smiled. That day, he said, is no longer imagination. Rabbi Newman had recently shared that in just the past few weeks, he attended several weddings where chaburos stood together learning. One even without Gemaras in hand, yet comfortably exchanging the shakla v’tarya of the sugya they were holding in.

And then R’ Nakash brought the vision to its boldest expression.

Ten years ago, he said, the hope was that through Kinyan HaMasechta, Mashiach would one day be able to greet a new Klal Yisrael—strong, connected, and alive with Torah. Standing here now, surrounded by what Kinyan has built, he said those words no longer felt like a hope deferred. This new Klal Yisrael is already here. And it is ready.

The formal program concluded with what was billed as a kumzitz with Eitan Katz. In practice, it became something else entirely. The singing quickly gave way to spirited dancing once again, as if the energy in the room simply could not be contained. Arms linked, circles formed, and the music became an expression of something deeper than melody—a reflection of the passion, connection, and shared feeling that had been building throughout the night.

And as the event drew to a close, it was hard not to think back to the sight that greeted everyone at the door—hundreds of worn Gemaros, softened by chazarah and filled with penciled notes, being carried back out into the world, ready to continue the work they were never meant to finish.

The night ended, as all nights do. But something lingered.

Not just inspiration, but resolve. Not just excitement, but belonging.

A family had gathered. A family had learned. And once again, quietly and powerfully, Kinyan HaMasechta had grown—not only in number, but in depth.

For more information, visit kinyanhamasechta.com

(YWN World Headquarters – NYC)