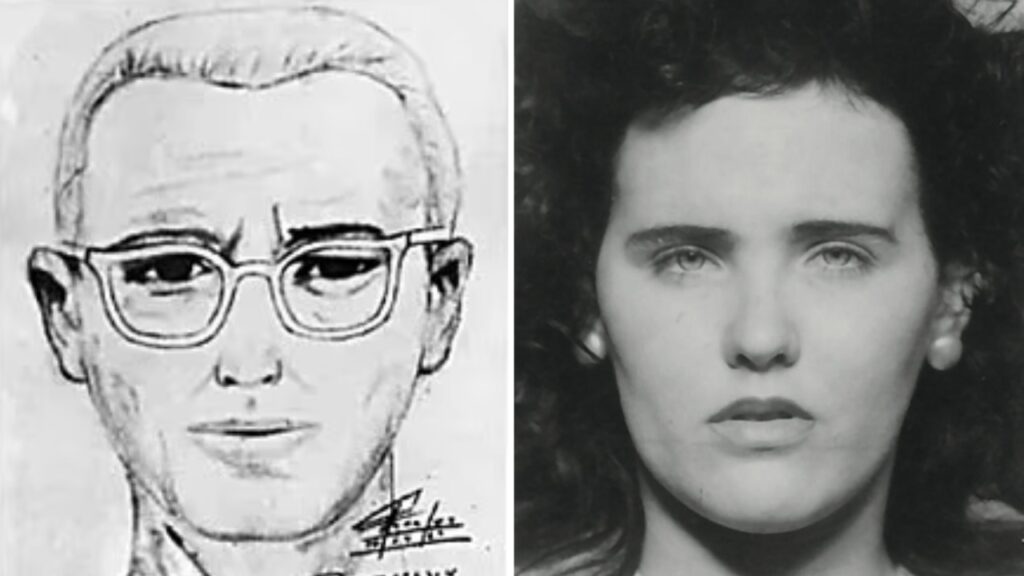

For more than half a century, two of America’s most infamous unsolved murders—the Zodiac killings and the Black Dahlia—have occupied a peculiar place in the national imagination: endlessly theorized, officially unresolved, and periodically revived by a new suspect or cipher crack that promises, and usually fails, to bring closure.

Now, an unlikely figure is insisting the mystery is finally over.

Alex Baber, a 50-year-old West Virginian with autism, no formal law enforcement background, and an obsession with cryptography, says he has identified the man behind both crimes—and that the answer has been hiding in plain sight for decades. His conclusion: the Zodiac killer and Elizabeth Short’s murderer were one and the same, a late Chicago-born World War II medic named Marvin Margolis.

“It’s my autism,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “Once I start on something, I have to see it through. The deeper I go, the harder I push.”

For months at a time, Baber says he worked up to 20 hours a day, using artificial intelligence tools and painstaking manual research to revisit the Zodiac killer’s most tantalizing clue: the 13-symbol cipher mailed to newspapers in 1970, taunting police with the words “My name is.”

Baber fed the cipher into an AI program and asked it to generate every possible 13-letter name. The result was overwhelming—roughly 71 million combinations. From there, Baber did what official investigators never could at scale: cross-referenced names against witness descriptions, geographic movement, census data, military records, and public archives.

The list shrank. Then shrank again. Eventually, it collapsed to a single identity: Marvin Merrill—an alias adopted by Marvin Skipton Margolis after he was investigated, and cleared, in the 1947 murder of Elizabeth Short.

Margolis’ proximity to the Black Dahlia case is not speculative. He lived with Short in Los Angeles shortly before her body was found bisected, drained of blood, and mutilated in a vacant lot—one of the most gruesome crimes in American history. Investigators at the time suspected the killer had medical knowledge. Margolis did.

A frontline Navy medic during World War II, Margolis served in the first wave of the Battle of Okinawa, where he was trained in emergency battlefield surgery—what was known as “foxhole medicine,” including amputations performed with combat knives. After the war, he sought to become a surgeon, but was discharged for what doctors described as severe psychological trauma.

A Navy psychiatrist’s report described him as “resentful,” exhibiting “open aggression,” and fixated on surgical techniques he was never allowed to master.

“He wasn’t a doctor,” said Rick Jackson, a former LAPD homicide detective who reviewed Baber’s work, “but he had done things doctors often do. He had a lot of experience dealing with the human body.”

Margolis was questioned in the Black Dahlia case but ultimately cleared, in part because investigators believed Short had been kidnapped days before her murder, a timeline Baber argues was wrong. Margolis later changed his name, moved repeatedly across the country, and eventually settled in California, where the Zodiac killings erupted two decades later.

That is where Baber says the coincidences turn unsettling.

Newspaper accounts from 1947 described a frantic man searching Compton motels for a room with a bathtub the night before Short’s murder. One of those lodgings was known at the time as the Zodiac Motel.

“That was the key,” Baber said. “To where she was murdered—and to his future moniker.”

Further links emerged when Baber contacted Margolis’ son, who showed him a Japanese bayonet his father brought back from the war, consistent with weapons speculated in Zodiac attacks and bearing a symbol eerily similar to one in Zodiac’s cipher. A year before his death in 1993, Margolis also produced a drawing titled “Elizabeth,” depicting a woman marked in ways that mirrored Short’s wounds. The word “Zodiac” appeared beneath the shading.

To Baber, the pattern is unmistakable.

“It’s irrefutable,” he said.

Not everyone agrees. Some skeptics argue Baber lacks academic credentials and accuse him of narrative overreach. One critic told the LA Times his work was “a lot of empty calories.”

But Baber has found unlikely allies in high places. Ed Giorgio, the former chief codebreaker for the National Security Agency, said Baber’s cryptographic work held up under scrutiny. And Jackson, the former LAPD detective, offered perhaps the most provocative endorsement of all.

“In my opinion, these are solved cases,” Jackson said. “There’s overwhelming circumstantial evidence. He’s left breadcrumbs all along.”

(YWN World Headquarters – NYC)

One Response

“Some skeptics argue Baber lacks academic credentials and accuse him of narrative overreach”

This is the most disturbing part of the article. “Credentials” matter more than facts in the good old USA. Like the PHD’s who are believed over parents in claiming that transing the kids is good for them. And like how I can’t freely buy medicine (completely out of pocket) for things like a strep throat infection without some medical “professional’s” script.

PHD’s should be nearing extinction with the rise of AI, but we will probably see the regulations about who is able to access it, and for which purpose, very soon. And then we will be told that only “trained and licensed professionals” know how to “safely” use it.

Their “proofs” will be a few outlandish exceptionally gruesome examples, and the Western World will give up yet another chance for freedom.